A family’s 10 year end-of-life struggle

by Joanne Faryon

Photos and video by Brad Racino

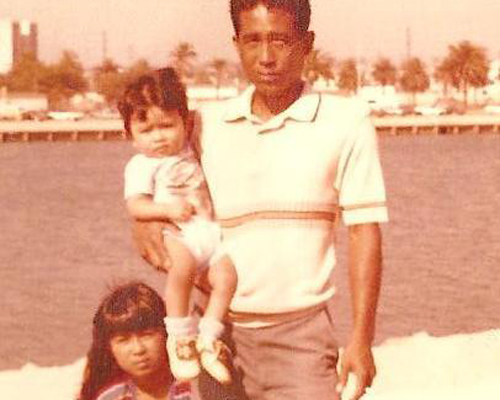

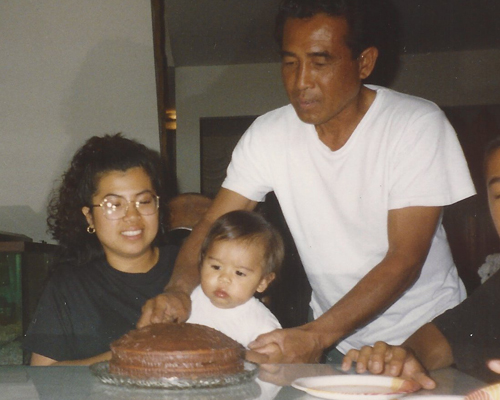

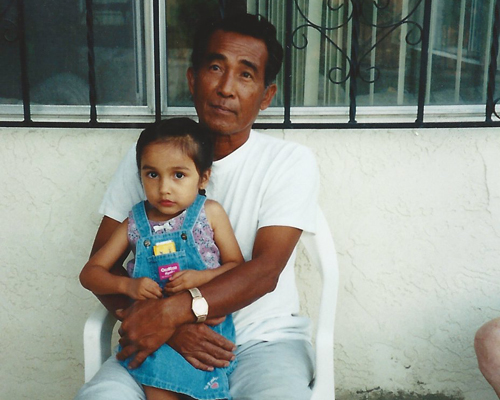

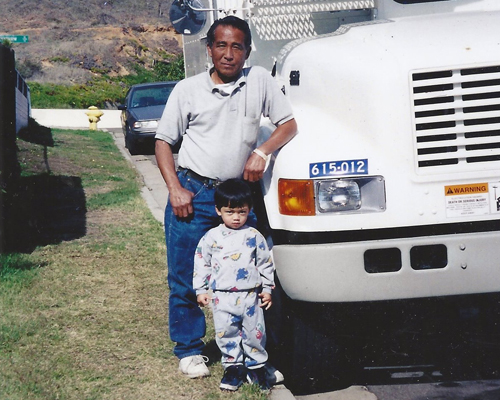

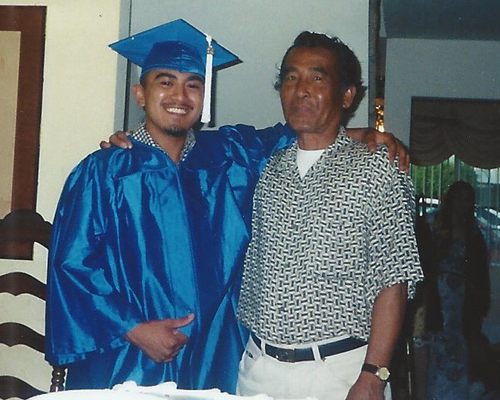

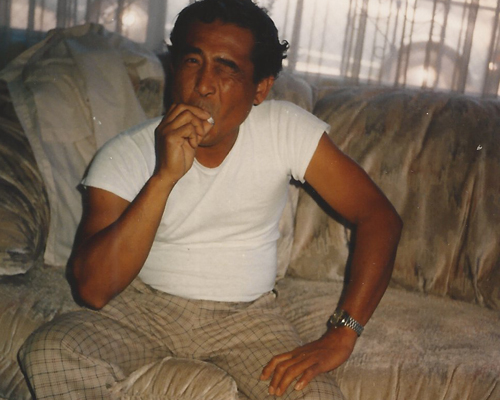

Pepito and Paulina Burlaza planned carefully for their retirement. He was a Vietnam veteran, electrician for the city of San Diego, father of four daughters and one son, and a handyman who taught all his children the difference between a Phillips and a flat-head screwdriver.

She was a schoolteacher and later a stay-at-home mom.

Their family grew together, as did their home, on a corner lot in a modest San Diego neighborhood. With the birth of each baby, Pepito found a way to make room. At first he added onto the back of the house, and then an entire floor when they had no where to go but up.

Theirs is an album of birthday cakes, Christmas trees, graduations, walks down the aisle, and grandchildren.

At 62, with Pepito newly retired, he and Paulina returned to the Philippines, the country where they met and married, to build their vacation home.

After nine months, with just the final coat of paint left to finish in the garage, Pepito had a stroke.

He was in a coma for weeks and eventually taken from a hospital in the Philippines to a nursing home in San Diego County. His family believed American medicine could do more for him.

“Everything was just hope,” said Elsa Burlaza, the second-eldest of Pepito’s children.

Pepito never fully regained consciousness. He lived in a vegetative state for 10 years. He was unable to speak, move, eat or breathe on his own. He had a feeding tube in his stomach and a tracheostomy tube in his throat.

Paulina spent hours nearly every day by his bedside. She never returned to their home in the Philippines.

The pension Pepito had carefully saved was used in part to pay for his nursing care. While he qualified for MediCal, the state’s program for the poor and disabled, his income was such that Paulina was required to pay a $1,100 monthly deductible.

Pepito was one of thousands of people in California kept alive each year with machines in special wards called subacute units. They are the end of the line, the place where modern medicine can keep you alive but where there is little hope for recovery.

Pepito didn’t have an advance directive, a document stating his medical wishes. He and Paulina never had a conversation about what to do if the other could no longer make health-care decisions for themselves.

With her faith and culture to guide her, Paulina did her best to honor what she believed her husband would have wanted. To be by her side, till death.

Pepito’s heart stopped beating in the early morning of April 14. Paramedics and ER doctors tried to revive him for 15 minutes before pronouncing him dead.

Elsa got the call.

The doctor told her they did everything they could to bring her father back.

“In my head I was thinking, ‘Why would they do that? He has a DNR,’ ” Elsa said.

DNR is short for Do Not Resuscitate.

The paperwork for Pepito’s DNR was never signed. Without one, first responders in California must try to save a life.

One in four people in California has an advance directive, a document spelling out their medical wishes, according to a survey by the California HealthCare Foundation.

The vast majority say they want to die at home and not be a burden to their families. But two-thirds have not put their wishes in writing because they either have had too many other things to worry about or didn’t want to talk about death and dying.

Most people are caught off guard when they have to make a major health decision for a loved one who has been in an accident or has had a stroke, said Teressa Vaughn, an advanced care planner with Sharp HealthCare.

It’s her job to talk to families of the critically or chronically ill who have little or no hope for recovery. Her work takes her to ICUs and nursing homes across the county.

“We’re running into the room of death when everyone else is running away.”

There is a common scenario in the cases Vaughn sees: an unexpected event, stroke or accident, and disagreement among families about what to do.

“They’re caught in that limbo. They feel like I must do everything,” she said.

“They don’t want to live with that guilt of maybe if I kept them on just two more days maybe they would have gotten better.

“The ‘maybes’ kill them.”

Sharp created its advanced care planning department a few years ago because doctors in its subacute (life support) units grew weary of families wanting everything medically possible done, including CPR, for dying patients.

One man in his late 80s was on life support, had severe dementia and advanced heart, kidney, and lung disease. He was being transferred back and forth between the nursing home and hospital. He eventually died from an untreatable bedsore when he was 90.

The case raised difficult questions for the doctors who treated him. Dr. Ken Warm was one of them.

“We really felt up against a situation of doing harm to people or going against family’s wishes,” Warm said.

Doctors didn’t believe providing heroic care to a dying man was a good use of their hospital’s resources, Warm said.

After that case, they began refusing to accept patients onto the unit who were dying and whose families wanted them to remain “Full Code.” That means they want everything done to save someone in severe distress, like cardiac arrest.

Half the people living on Sharp’s life-support units remain Full Code.

The two members of the advanced care team get referrals from doctors countywide.

Vaughn doesn’t try to persuade families one way or another. But she gives them a realistic picture of what life with a breathing and feeding tube might look like. And she’s careful.

“I’ve gone to many (ICU) rooms where it looks like that patient is not going to make it and within months this person is eating. They’re talking. They’re walking.”

Sharp is the only local health care company that has an entire department dedicated to helping people navigate end-of-life issues.

In most cases, the conversation Vaughn or a doctor has with a family is not reimbursed by Medicare or health insurance companies.

Those conversations were dubbed “death panels” during the debate over The Affordable Care Act, now often called Obamacare, a few years ago. A report released earlier this month by the Institute of Medicine, an arm of the National Academy of Sciences, is now urging insurance companies to reimburse health-care providers for these conversations, calling them “critically important.”

Most people aren’t capable of making those decisions when they are nearing the end of life, and so planning ahead is the best way to ensure the patients goals are aligned with the care they actually receive, the report states.

The American Medical Association has also asked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) this past May to create billing codes for these conversations. An AMA spokesman said it will be up to CMS to decide whether to cover the services.

Vaughn doesn’t let the negative term “death panel” get in the way of her work. She embraces it. Deciding how you want to live and how you want to die should be something everyone considers because everyone dies, she said.

“That’s going to happen to 100 percent of the people 100 percent of the time. Why not have a discussion, why not have a panel?”

Present when her own father took his last breath two years ago, Vaughn said she sees death differently from most people.

“It being such a sacred and spiritual event, I deem it an honor to be present to be a part of the process,” she said.

In the case of the Burlazas, it was up to Pepito’s wife, Paulina, his legal power of attorney, to decide whether to sign a DNR or keep him on Full Code.

“That was the one thing she didn’t want to do, was make that decision,” her daughter Elsa said.

Paulina believed her husband still had the ability to understand and know when she was in the room with him.

“Sometimes there are tears in his eyes,” Paulina said.

Watching him grow frail, afraid that CPR would hurt him, Paulina decided to change Pepito’s status from Full Code to DNR earlier this year.

“Baby steps,” Elsa said.

When she woke that morning in April and learned from her daughters that her husband had passed, Paulina felt peace.

“I think it’s time for him to be with God,” she said. “God maybe needs him now.”

At his funeral, Paulina held her husband’s hand for several moments and then bent down to kiss his cheek one last time.

Later she would tell her family that when she saw Pepito inside the coffin, no longer attached to tubes or machines, she felt his suffering was finally over.

“No more trach,” she said.

A month later, on Mother’s Day, all the Burlaza women gather in the family home to celebrate. It’s tradition for them to spend this time without their husbands and children.

There’s laughter, and on this Sunday, there is some debate over where they will have dinner later. The eldest daughter, Cathy, looks for the coupons for Soup Plantation.

Paulina sits in a chair just outside the kitchen as her daughters sit and stand in a makeshift semicircle around her. The topic of Pepito, his life and death, is unavoidable.

No one is talking about who will drive Paulina to the nursing home or whose day it is to visit.

“All of our lives were actually on hold because we had to dedicate time to make sure that she was able to see my dad,” Elsa said.

The girls turn their attention to their mother.

It’s her time now.

She wants to go to the zoo. She has not been since the kids were little. They’re also talking about making changes to the house. Paulina wanted everything to remain as it was while Pepito was alive.

The family is planning a trip to the Philippines to spend time in the house Pepito and Paulina built. A house that has been empty all these years.

After so many years of keeping vigil with her husband, it is a painful irony that Paulina is now not well. She has diabetes and kidney failure. She needs dialysis three times a week.

In a conversation with Teressa Vaughn at her daughter’s kitchen table just weeks before her husband’s death, Paulina made her own wishes known.

If she becomes incapacitated, “I want to die inside my house. Stop the dialysis.”

…

Joanne Faryon is an investigative reporter and producer at inewsource.

Joanne Faryon is an investigative reporter and producer at inewsource.

To contact Joanne, email her at [email protected].

Follow her on Twitter @JoanneFaryon.

Brad Racino is an investigative reporter, videographer, editor, producer and web designer at inewsource.

Brad Racino is an investigative reporter, videographer, editor, producer and web designer at inewsource.

To contact Brad, email him at [email protected].

Follow him on Twitter @BradRacino.

Lorie Hearn is the executive director and editor of inewsource.

Lorie Hearn is the executive director and editor of inewsource.

To contact Lorie, email her at [email protected].

Follow her on Twitter @LorieHearn.

FORUM

Have a question about end-of-life care or decision-making? Ask our experts by clicking here. Or, if you’ve had an experience with end-of-life issues, share your story here for possible publication on our website.

FAQ

The Impossible Choice team describes the origin of this project and the difficulties in reporting it here in our Frequently Asked Questions section.

DONATE

An Impossible Choice is a project of inewsource, an independent journalism nonprofit on the campus of San Diego State University. Find out how to support this kind of work here.