Deciding When a Life is No Longer Worth Living

by Joanne Faryon

photos and video by Brad Racino

It was the fifth time Rafaela’s feeding tube clogged, on the fifth consecutive Friday, that drove Steve Simmons to threaten to bring a shotgun into the nursing home.

He hadn’t been to work in the five months since their accident. He’d lost 30 pounds, and every day he spent hours by his wife’s bedside. Some days, he never left.

The chalky liquid in the tube, known as the “feed,” hardens like concrete if it isn’t in motion. Rafaela would have to be fed through a tube down her nose until doctors could insert a new one into her abdomen the following Monday. Steve couldn’t bear to watch another time.

Looking back, he believes he only intended to shoot himself.

“What I really meant was, ‘I’m going to come in here and blow my brains out in front of all of you. Because I can’t endure any more of this,’” Steve said.

Rafaela, 55, is severely brain injured. For the past four years, she has been kept alive with a feeding tube in her stomach and a breathing tube in her throat. She can’t walk or talk. It’s unlikely she knows who or where she is.

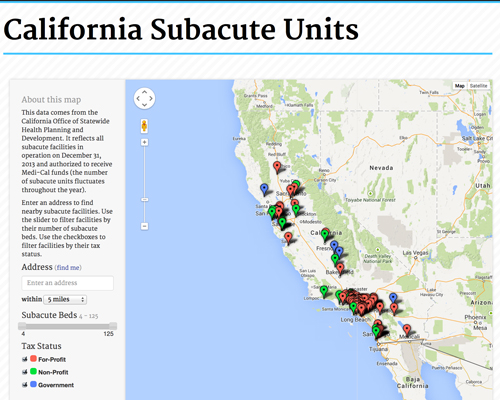

She is one of 4,000 men, women and children kept alive with machines in special wards in California’s nursing homes.

On the books they’re called subacute units. But among some doctors, they’re known as “vent farms,” shorthand for the ventilators that keep so many of the residents breathing.

The units are the end of the line, the place people go once medicine has saved them, but there is little hope for recovery.

The state of California created them more than 30 years ago to get life-support patients out of more expensive hospital beds. Now 125 subacute units operate across the state. Fourteen are just for children.

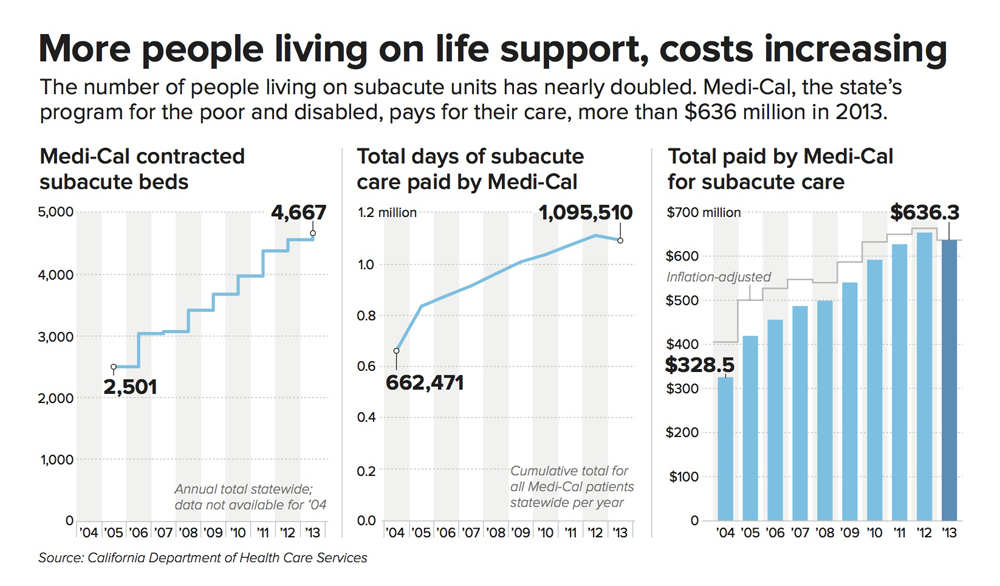

Medi-Cal, the state’s program for the poor and disabled, pays for most subacute care — as much as $900 a day. Last year, the total cost came to more than $636 million, almost double what it was in 2004.

While the cost is considerable, the human toll is staggering. Most people on these units will spend the rest of their lives in bed, their bodies twisted from muscle contractures, tubes permanently inserted in their throats and stomachs, completely dependent on others to brush their teeth, comb their hair and change their diapers.

The number of people kept alive by artificial means has nearly doubled in the past decade.

And there is the grief — heartless and relentless — of the loved ones left behind. Hoping for a miracle in the face of a grim prognosis, circumstances cajoling them into magical thinking, they stand by the bedsides of wives and husbands, fathers and daughters, waiting.

“She is my wife,” Steve said.

“I’m not going to desert her in her time of need.”

The number of people kept alive by artificial means has nearly doubled in the past decade, with advances in medicine now able to save people who years ago would have died. Doctors, sometimes afraid of lawsuits or pressured by families, are providing heroic treatment to people who have no chance of getting better. These doctors aren’t always paid to have, nor are they always willing to have, the difficult end-of-life discussions that a few years ago took on the politically charged name of death panels.

The default in the system is to keep people alive at all cost — it won’t let you die without your written permission.

Health care administrators and doctors say if the government weren’t paying the bill, so many people wouldn’t be living this way for so long — in some cases, for more than a decade.

An inewsource reporter and a photographer got a rare look inside one of the largest subacute units in California, observing for many days over a period of months.

Here, emotion and dispassion collide, and basic questions of our existence intersect: how we choose to live and how we choose to die.

And, significantly, who will make that choice?

For more than two miles, the Coronado Bridge snakes its way across the San Diego Bay, stretching across spectacular scenery: the Navy shipyards to the south, sailboats and sandy beaches to the north. On the other side of the bridge is the city of Coronado, one part resort and one part military town, where armed Navy personnel stand guard at the southerly edge of one of the most stunning beaches in the country.

The Villa Coronado Skilled Nursing Facility is just a right, left, and right turn after the bridge, part of a larger complex run by Sharp Healthcare.

Subacute 2, one of Villa Coronado’s two life-support units, is housed in an old wing of the small hospital. It’s a 1949 single-story brick building surrounded by gingerbread-trimmed homes and porch swings.

From the inside looking out, an occasional car drives by, a woman cuts across the lawn with a dog on a leash, tree branches nod to the breeze blowing off the bay, some 400 yards away. It’s a panorama of ordinary life out of reach for nearly everyone on Subacute 2.

It’s morning, and there’s a steady flow of nursing assistants.

Some are wheeling green oxygen tanks to and from rooms; others carry the bags of liquid feed marked “fiber source.”

Fresh linen is piled at each bedside waiting for the team of workers to lift and roll in tandem. The smell of dirty diapers mixes with what might be lavender from the aromatherapy in the multipurpose room down the hall.

On this day in May, there are 62 men and women living on Villa Coronado’s two life-support units. Most are here because of brain injuries from car and motorcycle crashes, falls, fights and strokes.

The average age of people who live in subacute care is 56.

Some people have chronic progressive illnesses. Often it’s ALS. One 54-year-old woman born with severe cerebral palsy has lived here for 10 years.

The average age of people who live in subacute care is 56.

Some live on these wards well over a decade. The healthier the heart, the longer they survive.

Down the hallway, the doors to the rooms are all open. It’s hard not to stare.

The old woman …Her thin skin stretched tightly across her cheekbones, her mouth open as if locked in a scream …

Men in their 20s and 30s and 40s… Three to a room, three feet apart … Light blue tubes tethering humans to machines …

The TVs are on. SpongeBob, Mexican soap operas, a boxing match … No one is watching. Their eyes — some open, some closed — face the ceiling.

Most of the people here are in a vegetative or unresponsive state. That means they don’t react to people or stimuli. Touch. Sound. Smell. They have not tasted food in years.

They spontaneously smile and cry. It’s a cruel trick of the brain stem. To families, it looks like emotion, but doctors say most of the time, it’s a reflex.

There is a constant hiss from the oxygen equipment, like when an air mattress is slowly deflating. It’s punctuated by a choking-gurgling sound. A healthy person clears mucus by swallowing or coughing. For people with a tracheostomy — a breathing tube in their throat — the mucus gets trapped in their lungs. It has to be suctioned several times throughout the day.

The procedure is life-saving. A plastic tube, about the diameter of a pencil, is hooked to a small vacuum-like device, and then placed deep into the tracheostomy hole in the throat.

“Rafaela, we’re going to do trach suctioning,” the nursing assistant says as she reaches for the plastic tube on the wall behind the bed. It’s routine for staff to talk to the residents even though almost no one can answer back.

Rafaela’s body jolts up as the thin tube is inserted more than an inch into her windpipe. She makes a sound as though she is gasping for air.

“I feel it every time I see it,” said Dr. Ken Warm, Rafaela’s doctor. He is one of six on the unit. “How frightening it would be to have a tube in my lungs. And I can’t catch my breath, and I’m coughing, and someone is doing that to me. I can’t move my arms to push it away.”

Whether Rafaela or the others on the ward feel pain or the discomfort of a suction tube is not clear. Doctors rely largely on what they observe as indications of distress: a grimace, increased blood pressure or rapid pulse.

“Reflecting on that can be horrifying,” Warm said.

Warm, 62, has practiced medicine in Coronado for 34 years. He began his career delivering babies and eventually switched to geriatrics when malpractice insurance in obstetrics escalated.

Twice, he’s been chief of staff at the Coronado hospital. The first time was when the small hospital was struggling financially. In the 1990s, a private company offered to partner with it and manage the subacute unit, sharing the profits.

Subacute made so much money it subsidized the hospital’s emergency room and surgical unit.

It made so much money it subsidized the hospital’s emergency room and surgical unit.

“And that was what got us addicted, if you will, to subacute,” Warm said.

The hospital has since dissolved that partnership and entered into a new one with Sharp, a nonprofit. These days the unit isn’t as lucrative as it once was, with costs going up, Warm said. But getting out of the business is much harder than getting into it. The unit employs dozens of people and still turns a modest profit.

On a day in August, Warm met with a kidney specialist who plans to join the subacute staff. Some of the residents have developed kidney stones the size of golf balls.

They’ve stopped using their bodies and are no longer weight bearing, “like astronauts,” Warm said.

The calcium leaches out of their bones and gets reabsorbed into their system, forming large stones in their kidneys. They are too big to dissolve or surgically remove. Sometimes, they’re so big they stop the kidneys from working.

That means there will be another machine available to sustain lives on the subacute unit.

“The patients on ventilators who also have kidney failure can now get dialysis,” Warm said.

Rafaela’s wedding photo sits on the nightstand next to her bed, along with a clock radio and a Tiffany lamp, small signs this corner of the room is home.

Steve towers over her 4-foot-11-inch frame in the photo. He is wearing a tuxedo, a white rose on his lapel and a proud grin. Rafaela has flowers in her short, dark hair. Her brown eyes are wide, her lips open, but she’s not smiling. There is magic in a photo more than 20 years old, able to capture the intersection of hope and uncertainty.

Steve pulls the blue curtain to separate his wife from her two roommates. He sees it for the flimsy shield it is, but has learned to find intimacy where he can.

There is just enough space between the bed and the wall for Steve to stand while he holds his wife’s hand or combs her hair or reads to her from a prayer book. Not a religious man before the accident, Steve turned to the Bible in the aftermath. Without it, he doesn’t think he would have survived. If medicine and time can’t bring Rafaela back, perhaps God will.

“Squeeze my hand if you love me,” Steve asks his wife.

On this day, no matter how many times he asks, Rafaela does not squeeze.

In all likelihood, Rafaela will die in this room. Most people who come to Villa Coronado’s subacute unit never get better. On average, they’re here for six years.

Some live much longer, like the young man who arrived when he was 16 and has been here more than a decade. Two men in their 80s have been here for 15 years.

“I can remember the night before the accident,” Steve said.

“We were sitting on the couch and we were watching a movie.”

He tries to remember the name. They’d seen it before. A love story with Christopher Reeve. Reeve travels back in time, meets a woman and then loses her when he returns to the future.

“He so desperately wants to go back to that woman, and he can’t.”

Steve aches for the woman he’s lost:

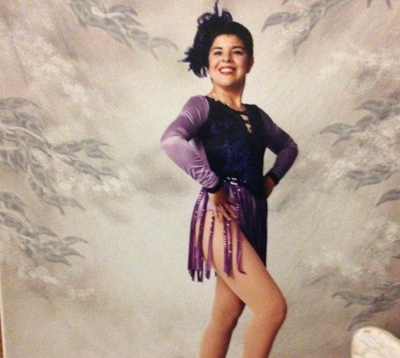

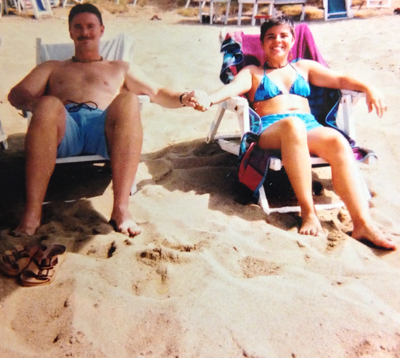

A 107-pound “ball of fire.” She liked to be called “Rafie.” She made jewelry from colorful beads and sold it at street fairs. She danced — her favorites were jazz and tap. She cooked, traveled, exercised and loved the beach. She was the assistant manager at the United Nations gift shop at Balboa Park.

“Even if she were to recover, to be able to walk, to relearn how to talk, how to write, the slate has been wiped clean. She will never be that person,” Steve said.

It took only an instant for her to disappear. A driver who didn’t see them coming.

Steve loved riding motorcycles. The plan on this Sunday morning in February, Valentine’s Day, was to ride with friends along the coastal highway to Oceanside, about 45 miles from downtown San Diego. They would have lunch and then head back to the city.

At first, Rafaela didn’t want to go, but Steve persuaded her. He wasn’t going more than 25 mph. She was on the back. A car pulled out in front of them from a side street.

They almost made it past, but the front tire of the motorcycle caught the rear bumper of the car. Steve was tossed to the ground, hurt his shoulder and broke his wrist. She was thrown.

Rafaela was wearing a helmet. Steve isn’t sure how she landed.

She spent 27 days in the ICU. Her brain was so swollen a monitor was inserted into her skull to measure the intracranial pressure. Another two millimeters and she would have been dead.

A team from the hospital told Steve that Rafaela would probably never recover and offered hospice care. But a neurologist consulting on the case offered Steve hope instead. He said Rafaela was a “fighter.”

“He said, ‘You have to take one day at a time. I can give you information based on studies, based on statistics, but every case is different,’” Steve recalled.

It’s what Steve wanted to hear. He looks back and knows he made an emotional and not a rational decision by refusing hospice, but as a husband who didn’t want to lose his wife, he was given an impossible choice.

The first time Steve hears the words life support in connection with Rafaela is during our third interview.

“I have never heard a physician, I’ve never heard a nurse, I’ve never even heard a family member on subacute use the term life support. I think we all kind of know it in the back of our minds. We just don’t want to acknowledge it,” Steve said.

“The mind is powerful. It protects you.”

Steve thinks about it some more and acknowledges that without a feeding tube, his wife would die. But he insists she isn’t like the others on the unit who lie in bed all day staring into space.

“That’s not my wife. Most of the people on subacute do it. My wife doesn’t do that.”

Medi-Cal pays for subacute care. Most private insurance will only pay for the first 100 days in a nursing home. The monthly bill — which can range from $15,000 to $30,000 — prevents just about everyone from paying out of pocket.

One week on life support can cost more than an entire year of health care for the average person enrolled in Medi-Cal.

One week on life support can cost more than an entire year of health care for the average person enrolled in Medi-Cal.

To be eligible for Medi-Cal, residents and their families spend down savings and liquidate assets. Some families take out reverse mortgages; others turn over entire pension or disability checks to cover the cost of their Medi-Cal deductible. Steve had to legally separate his assets from his wife’s so she could qualify.

There is no Medi-Cal cap for subacute care. As long as residents remain disabled and poor, the government will pay.

A tracheostomy and a feeding tube automatically qualify someone to be admitted into subacute care. They’re often referred to as trach and PEG (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy). It’s rare to have one tube without the other.

Hospitals and doctors are paid to perform both, between $200 and $700 for a tracheostomy and as much as $1,000 to insert a feeding tube.

“It’s a hell of a lot easier to trach and PEG,” said Dr. Jay Rosenberg, a San Diego neurologist who helped establish the American Academy of Neurology’s guidelines for persistent vegetative state. He’s also written about the life-and-death decisions families face after a severe brain injury.

It’s time-consuming and more difficult to have a conversation with families about whether they should stop treatment, Rosenberg said. “These discussions are gut-wrenching.”

He’s had many of those talks over the course of his 40-year career. Once a hospital was getting ready to trach and PEG a 91-year-old woman who had just had a massive stroke.

He spent an hour with the family, told them she would never recover and asked them what she would have wanted.

“They let her pass peacefully. Did that hour make a difference? It must have made some difference,” Rosenberg said.

He wasn’t able to bill anyone for the time he spent with the family.

Click to read Politifact’s

“Lie of the Year”: Death Panels

& the story behind the two words

that ignited a national debate over health care.

Paying a doctor to talk to people about end-of-life issues became political in 2009 when the expression “death panels” came to mean the government would decide who should live and die.

Former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin coined the term, describing a provision in the newly proposed health care law, often called Obamacare.

The proposal would have allowed doctors to bill Medicare for the time they spent talking to patients about their medical wishes if they had a terminal illness. The term death panels generated so much bad press the provision for those discussions was eventually removed.

A report released two weeks ago by the Institute of Medicine, an arm of the National Academy of Sciences, urged insurance companies to reimburse health-care providers for these conversations, calling them “critically important.”

The American Medical Association also asked the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) this past May to create billing codes for these conversations. An AMA spokesman said it will be up to CMS to decide whether to cover the services.

In a recent article in the Journal of Palliative Medicine, UC San Diego researchers wrote that doctors are abdicating their responsibility even when these conversations do happen, often not telling the whole truth about a prognosis because it’s “uncomfortable.” The researchers also said doctors — sometimes out of fear of being sued — are putting too much of the decision-making into the hands of patients and families. Asking them to decide when to stop treatment is like asking someone to “pull the plug,” they write.

“No one wants to be responsible for ‘killing’ someone.”

Google has also complicated things, with people rejecting medical opinions and instead believing what they find on the Internet, said Dr. Warm.

“What’s changed is the broad availability of information. But the information doesn’t come with an indicator of how accurate it is.”

Read

“Reconnecting Terry”

from ArkansasLife

Warm has heard his share of so-called miracle cures. And the “miracles” themselves, like Terry Wallis, the man who spoke after 19 years in a minimally conscious state. His first word was “Mom.”

Researchers believe his damaged brain was able to form new connections.

More than 10 years later, Wallis is fully conscious, but remains profoundly disabled.

Families read the stories about Wallis — “Coma man wakes after 19 years” — and believe if they just wait long enough, the same could happen to their husband, wife, brother or sister.

They have infinite hope in the bleakest of circumstances, seeing small gestures — a grunt or the batting of an eyelash — as signs the person they love is slowly coming back to them.

“I saw (early on) that if I tried to give my opinion that we shouldn’t go on, that made them less able to have me be a source of information,” Warm said. His opinion was seen as an agenda.

So he’s learned to be patient.

“I need to communicate that low probability (of recovery) with the family and be with them in their vigil, if you will, and have them slowly, sometimes over decades, come to terms with what they’re faced with.”

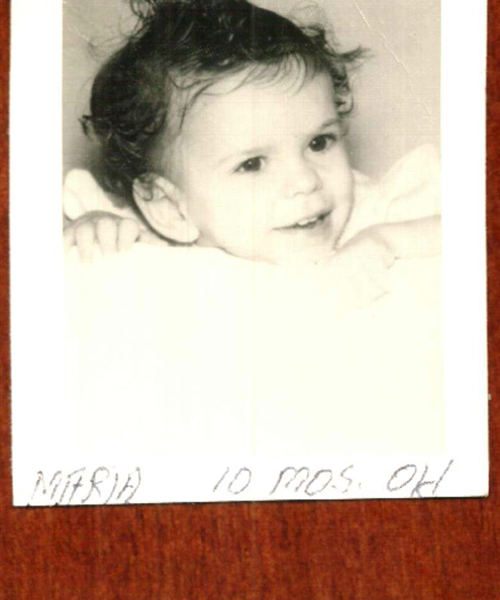

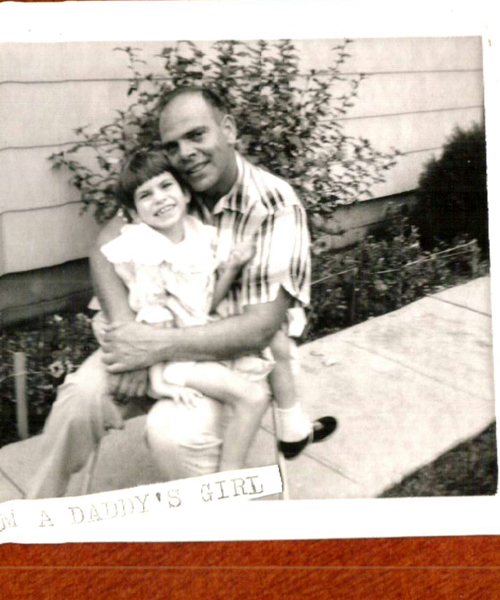

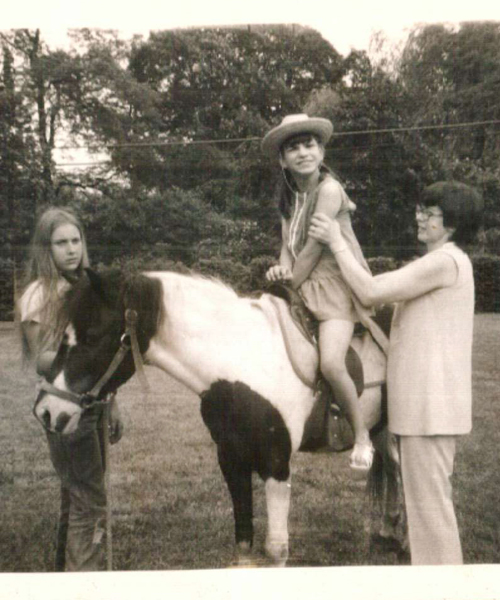

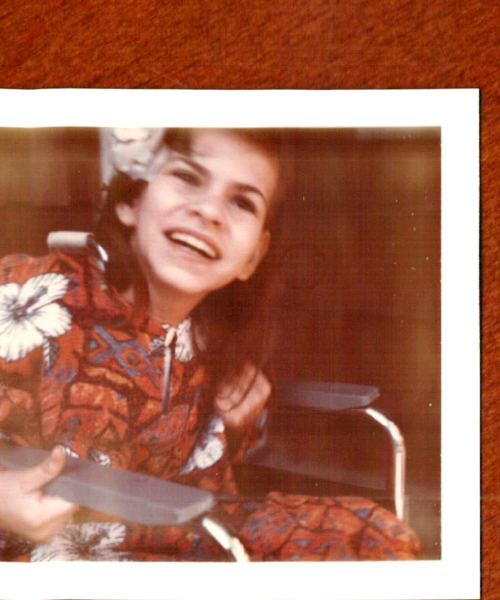

Maria Curcio lives three doors down from Rafaela Simmons.

She is tiny, less than 100 pounds, with dark brown hair her mother puts in pigtails, and deep-set brown eyes. The odd configuration of her room, the last in a long row, means she has just one roommate instead of two — a young woman so still and silent in her bed, it’s easy to forget she is there.

Maria’s end of the room is decorated with balloons, stuffed animals and a leftover tree from Christmas, one of her favorite holidays. She has stacks of old movies that play on the television on the wall across from her bed. There are old photos, birthday cards and a “we love u kid” sign on the bulletin board above her dresser near the window.

Maria is 54 years old. She has lived in this room for 10 years. She has a urostomy tube to drain her bladder, a feeding tube and a tracheostomy.

She is one of the 17 people who live on this unit because of illness rather than an accident or stroke. Many have ALS, some have cancer and some have dementia.

She is one of eight — out of 62 on the unit — who are aware of their surroundings. She responds to what she hears and sees and feels with the expression on her face. She sometimes smiles when her mother teases her. She winces and gestures as if to cry out when she is in pain, which lately is every day.

Maria was born with spastic quadriplegia, the most disabling form of cerebral palsy. She has never walked and has only limited use of her left hand. She has never spoken.

When she was born, doctors had so little confidence she would live more than a few days that she was baptized in the hospital. Maria couldn’t suck from a bottle, but her mother, Nancy Curcio, found a way to feed her, squeezing drops of formula from plastic bottles.

Sometimes it took hours. If she squeezed too fast, Maria threw up. Too slow, and she fell asleep.

“It was like a part-time job,” Nancy said.

At 9, Maria began eating regular food but only if it was cut into very tiny pieces. Nancy learned to carry a serrated knife in her purse whenever they left the house. By 27, Maria needed a feeding tube.

Cerebral palsy impacts muscle control and can affect intellectual development. It’s caused by brain damage, usually before birth.

A lifetime of the disease has contributed to a host of serious medical afflictions: Maria has kidney stones and respiratory failure. She takes 30 medications, most of which are crushed and put through her feeding tube.

Her right hip is so tightly contracted it causes her knee to bend into her chest.

Last year surgeons cut through her thigh bone to release it from her hip, but the surgery gave her little relief.

The pain is so bad Maria has begun to make deep, agonizing sounds that can be heard down the hallway of the nursing home.

And she’s taking so many pain medications staff had a special meeting to talk about whether they should scale back the doses.

“It’s getting harder and harder because basically if I was in that condition, I would give it up,” Nancy said.

Nancy makes all of her daughter’s health-care decisions. Now, with Maria growing weaker, her pain unbearable, Nancy is facing the most difficult choice: contemplating life without Maria. It is a burden so onerous she looks for signs from Maria about whether she wants to live or die.

There are times when Maria smiles, and then, to her mother, she looks more like the happy little girl in so many of the Curcio family photos than the middle-aged woman she is now.

Or she blows a kiss to a reporter to say goodbye after they meet for the first time.

For Nancy, it is evidence Maria continues to find joy in life.

“I cannot pull the plug on somebody like that who expresses the fact that they’re not ready to give up.”

It’s difficult to know whether it’s Maria or Nancy who is not ready to give up. Nancy has become so accustomed to giving her daughter a voice — so afraid that she would not be given choices in life because she couldn’t speak for herself — that even she may not be sure who is speaking now.

From selecting the movie her daughter wants to watch to deciding whether she needs a painkiller, Nancy finds a way to ask Maria.

She holds a DVD in either hand, both old “Blondie” movies, and asks Maria to look in one direction or the other.

She asks if she is in pain, looking right means yes, to the left is no.

“I think it’s a horrible position to be in, to make the decision for someone else. Especially someone else who understands what’s going on,” Nancy said.

“(Maria) just seems to want to go until the very end.”

Where the end is, the line that separates a life worth living from one that is not, is sometimes hard to see.

Nancy is hoping another hip surgery will help her daughter and has written a desperate plea to the surgeon who performed Maria’s last operation.

She is asking that he reconsider severing all the muscles and tendons of her daughter’s leg from her hip, a procedure Nancy said he initially refused to do.

“I know you did not totally disconnect the leg as was planned because you had sympathy and empathy and meant well — the word you used about it was gruesome,” she wrote to the doctor in August.

“I hate to put her through more surgery, but the past year watching her writhing in pain, sleeping off the result of pain or pain medication & being bed-bound has us rethinking what is the right thing to do,” Nancy wrote.

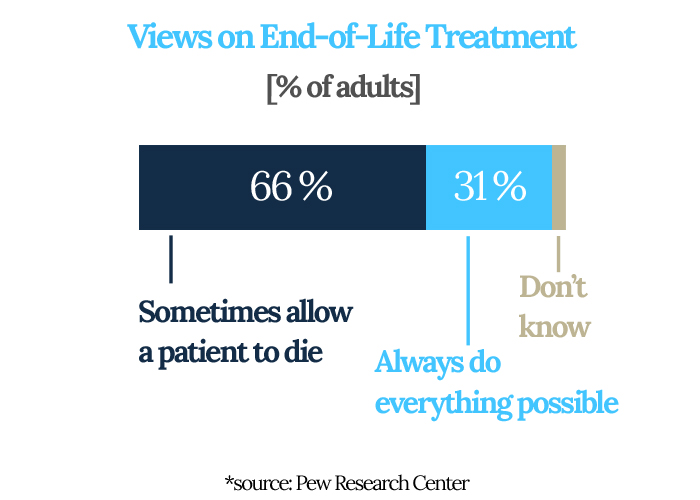

A majority of Americans say there are some circumstances in which doctors should allow patients to die, but a growing number believe they should do everything possible to keep them alive in all cases, according to a Pew Research study released last year.

These are statistics health researchers are paying close

attention to, as advances in medicine can save people

who decades ago would have died, and as an aging

population puts pressure on a health-care system that

continues to consume an increasing share of the

country’s GDP.

Joan Teno is a professor of medicine and associate director of the Center for Gerontology at Brown Medical School. She’s an expert on medical care for the dying.

Even she was surprised to learn California had such large concentrations of people living on life support in nursing homes.

Teno said it’s one thing for people to knowingly want to be kept alive under dire circumstances; it’s another if they’re on life support because no one, not they or a family member, has made an informed choice.

“Right now, all our financial incentives are aligned with doing more,” Teno said. “They’re all aligned with just continuing to hospitalize these patients and not ask what the goals of care are.”

For example, in California, when nursing home residents on Medi-Cal are transferred to a hospital for treatment, the state continues to pay the nursing home hundreds of dollars a day for the empty bed.

It’s called a “bed hold.” It’s done so residents don’t lose their place at a nursing home when they’re hospitalized.

But it results in another financial incentive to send the patient to the hospital, rather than have a conversation about whether treatment is the best option, Teno said.

“By far, the easiest thing to do in the middle of the night is send them back to the acute care hospital.”

Across the country, 70 percent of all skilled nursing facilities are for-profit operations, earning profit margins between 12 percent and 24 percent in recent years, according to a 2013 report by Medpac, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, which informs Congress.

An inewsource analysis of all skilled nursing homes that provide subacute care in California shows 80 percent are for-profit enterprises. (Villa Coronado is a nonprofit.)

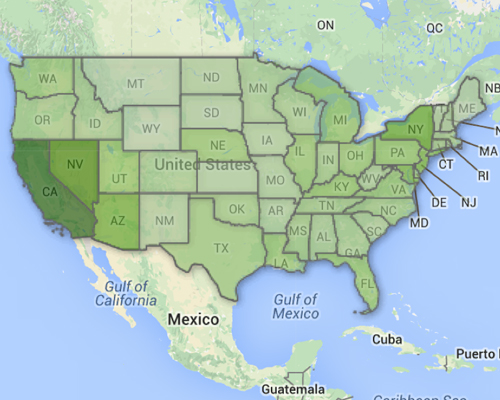

National Life Support Statistics

Explore life support statistics nationwide in this interactive map.

inewsource could not find an agency on a national level that tracks a population like those in California’s subacute wards.

Without surveying every state, it was not possible to determine whether other places have similar laws defining the population and establishing financial payment for care.

On a given day, about 13,000 people… are kept alive by a ventilator or tracheostomy and a feeding tube. One-fifth are in California.

To get at least a snapshot of people in this country on life support, Teno agreed to analyze her data of people living in nursing homes who are covered by either Medicare or Medicaid.

She found that on a given day, about 13,000 people, or 1 percent of these nursing home residents, are kept alive by a ventilator or tracheostomy and a feeding tube. One-fifth are in California.

Rosenberg, the neurologist, wonders whether so many people would decide to keep loved ones who are unresponsive, with no hope of recovery, on life support if they had to pay the bill.

“The issue I think has to do with some degree of responsibility. But the way society has set it up, this is the way it is,” he said.

One afternoon in May, a woman plays the piano in the activity room. There are six men in wheelchairs across from her, all of them attached to oxygen machines. Vapor swirls around one man’s throat. From a certain angle, with the sound of the piano, in any other place, it might be mistaken for cigarette smoke.

“I sure missed you when I was gone,” the piano player, a regular volunteer, tells the men in between songs.

No one claps. They can’t. The only man able to respond, the one in the middle, moves his thumb against his pinkie in a slow-motion version of the tune.

On the wall, alongside the Cinco de Mayo decorations, is a picture of the resident of the month. Ed Kirkpatrick, the director of Villa Coronado, points to it and tells a story about the man’s distinguished military career. That’s the thing about Villa Coronado; it’s a lot about who you used to be.

Kirkpatrick is a big guy with a North Carolina drawl, a director of nursing for much of his career. He was among the last group of teenage boys to be drafted for the Vietnam War, and there’s a kind of military exactitude in the way he describes his mission at Villa Coronado.

“Our objective is: Don’t get infections, don’t get skin breakdown, don’t get pneumonia,” Kirkpatrick said.

Those are the things that eventually kill people on this unit.

He’s been in his job a little more than two years and has gotten to know the families of the people who live here.

Many spend hours and some spend entire days at the nursing home, sitting, praying, waiting.

It’s a vigil often driven by guilt.

“I might not have been as good a child or as good a parent or a husband or spouse as I think I should have been, but I’m going to do everything I can to make sure that we keep you alive,” Kirkpatrick said.

As an ICU nurse and now on a subacute unit, Kirkpatrick has seen how everything can change in an instant, forcing people to make one of the most important decisions of their lives under duress.

“Generally, a lot of people haven’t thought about what am I going to do if I’m in a head-on collision today and I’m not capable to speak or make decisions for myself.”

Most people don’t have an advance directive, a document stating their medical wishes. Without one, the system will do everything medically possible to keep people alive, Kirkpatrick said.

“And that’s a good thing. We want that to happen. At what point, though, does it become” — he pauses for a long time — “futile?“

It’s after 5, and from his small office window at the side entrance of the nursing home, Kirkpatrick sees Steve Simmons arrive to spend another evening with his wife.

For the first year after the accident, every day Steve wanted to die.

The night he threatened to bring the shotgun to the nursing home, the head nurse called police and Steve voluntarily turned himself in at the station. Staff decided not to press charges. It wasn’t the first time they felt threatened by desperate family members. They came up with a visitation plan for Steve that included being escorted by security over the next several months.

Steve describes other breaking points. The time the electrodes for Rafaela’s brain wave test wouldn’t stick to her head the way they were supposed to. Steve watched as the technician tried to glue all 34 of them, pressing hard against Rafaela’s scalp, her coarse hair rejecting them in the only act of defiance of which her body was still capable.

“I can see people who come here for the first time, and my heaven’s sake, they’re shaking.”

Driving home late that night, the bridge nearly deserted, Steve stopped his car.

But if he jumped, who would take care of his wife?

Steve now sees a therapist, works long hours and a few days a month camps in solitude. His days feel like an endless loop, and just when he thinks he’s used to it, something or someone, maybe an old friend who asks about Rafaela, sends him into a freefall.

He realizes where he is and it’s terrifying.

“I can see people who come here for the first time, and my heaven’s sake, they’re shaking. They get a glimpse of one of the rooms and they won’t stop staring. You don’t see this. I had no idea it existed.”

Steve has never stopped feeling guilt — for being the one driving and persuading Rafaela to come for a ride when she wanted to stay home.

He searches his memory for a time when they might have had a conversation about what to do if something ever happened to one of them. He’s sure they talked about quality of life — if one or the other had none, what would they do? He believes since he refused hospice when Rafaela was first in the ICU, the moment to make the decision to let her go has passed.

“I’m thinking about Dr. Kevorkian and all these things, and I’m thinking you can’t kill people.”

In California, a patient or their next of kin can stop treatment and disconnect life support at any time. They can refuse antibiotics for an infection and can even withhold food and water.

Steve knows about the law. He found out about it many months after the accident when he heard one of the residents had been taken off his feeding tube. He asked a nurse if it was true.

“So they can do that? Just take you off the feeding tube and put you in hospice and medicate you.”

“And she said, ‘Yes.’”

Sometimes Steve says fate decided to keep his wife alive — she survived in the ICU, so who is he to change that?

“I really believe that if my wife could answer, ‘Do you want to stay alive, or do you want to die?’ I believe that she would say that she wants to stay alive. I believe that,” Steve said.

And if it were him?

“I’d want to go. I wish it were me. I wish it were me. I wish it were me. I asked for that so many times.”

In her kitchen, away from Maria and the nursing home, Nancy Curcio allows the weight of her situation to sink in.

What catches her off guard, all these years later, is a song from the old United Cerebral Palsy telethon. Not a woman prone to tears, Nancy fights them back as she recites the chorus.

Look at us, we're walking

“Look at us, we’re walking; look at us, we’re talking, we who’ve never walked or talked before.”

She remembers singing it to Maria when she was a child.

“And it struck me that I’m playing mind games with myself. I’m not admitting how much the talking….” Nancy still can’t say it. How painful it is to never have heard her daughter’s voice.

Nancy has devoted herself to giving Maria an ordinary life under extraordinarily difficult circumstances.

Maria has been both the Virgin Mary and an apostle in church plays, and she has gone to the Ice Capades, the rodeo and Radio City Music Hall. She’s been to birthday parties and dressed in costume nearly every Halloween. She traveled to Boston on a school trip and to Washington, D.C., where she met the first lady when Jimmy Carter was president. She was on the front page of her local newspaper when the community rallied to raise money for one of many surgeries.

When Maria was 9, Nancy drew letters on a large board that she placed across Maria’s wheelchair. She showed her how to move her left hand in the direction of a letter and eventually spell out a word.

But now Maria is in so much pain, she is unable to sit up. The muscles in her shoulders have grown so weak, she can’t always move her arms.

“She is losing the little she had,” Nancy said.

Now, more than anything, Nancy relies on Maria’s face, her expressive brown eyes, to communicate. It’s a code between mother and daughter refined over five decades of life together, one rarely apart from the other for more than days at a time.

Nancy believes most people wouldn’t want to live if they were in Maria’s situation because they would go from being able to do almost everything to doing almost nothing.

But for Maria, it’s different.

“We’re talking about somebody who never walked and never fed herself.”

One of the ladies from church has told Nancy maybe Maria is hanging on for her sake and she needs to know it’s OK to let go. Nancy thinks about it.

“She is probably 98 percent of my life,” she said.

From the car she’s driven (always a van so she could fit in a wheelchair), to the clothes she wore (something loose on top so she wasn’t restricted when she carried Maria), to the places she would go (because in the beginning they weren’t all accessible), Maria influenced everything.

At 78, Nancy is at a crossroads. Her daughter may outlive her.

“Every time I say my prayers, I pray that her death will be peaceful, that she will not be afraid or alone, and that she will predecease me — no hurry, God,” Nancy said.

She wants Maria to die first. Otherwise, she will become like the others no one visits on the unit — men and women, alone or forgotten, existing in a stillness broken only by the staff who care for them or the volunteers who play music or sing to them.

Maria has a sister and brothers out of state, but they have their own lives to live, Nancy said. They can’t be here every day to brush her hair, watch movies with her and give her a connection to the world outside her room.

“If I’m not here, she will be one of those people that will be a shell of a body lying in a bed.”

It’s a fear worse than death for Nancy.

Nancy has made another letter board, this one much smaller than the first, so Maria can use it in bed. There are times when Nancy puts it in front of her and Maria’s hand barely moves.

“Is it H? The letter H?” Nancy asks.

For nearly five minutes, Nancy holds the board, but eventually it’s too tedious and discouraging, and she puts it away.

But there are other times when Nancy asks Maria to focus, to think about what she wants to say. Maria purses her lips and it takes nearly a minute before her hand moves toward the letter “M.”

Another 10 seconds and her thumb touches the “O.”

Nancy sees what Maria is trying to spell.

“Mom.”

“Thank you very much. I love when you do that,” Nancy tells Maria.

She leans in close and kisses her cheek.

Warm examines Rafaela. He listens to her heart and checks her lungs. He picks up her right hand and asks her to squeeze, but nothing happens. Her eyes are open, and she blinks often. She is more alert than usual, Warm said. He believes she is aware he’s in the room, but he has no way of knowing. There’s no test or scan that can tell him.

In the past year, Warm has seen signs Rafaela is sometimes able to respond to Steve in small ways. Grasp a doll when he places it in her hand and move a finger. They are the smallest of gestures, but for Steve, they are proof of life.

One day in March, Steve leans in close to Rafaela. “Beso,” he tells her. Kiss. And it looks as though she kisses back.

“Otro beso.” Another kiss. And she does it again.

Warm doesn’t know whether Rafaela purses her lips out of reflex or whether she is responding to her husband.

“It’s ambiguous,” he said.

Steve sold the condo where he and Rafaela lived so he could pay for a full-time caregiver to be at the nursing home while he is at work. He wanted someone to talk to Rafaela and read to her. Someone to be with her to shave her legs when staff takes her to the shower room. Someone to check her skin for sores. Someone to make sure she is put in a wheelchair at least once a day, an effort that requires a hydraulic lift.

He reads everything he can on brain injuries and researches new treatments. He adds supplements to the long list of pills that are crushed and then poured through her feeding tube. He’s learned to cut her hair the way she liked to wear it and smoothes lotion with her favorite scent on her arm. He places the bracelets she made on her wrist.

With all of this, in the corner of the room that is theirs, for the hours that he is with her, she is Rafaela.

It’s in the silent, dark moments of the long ride home, as the blackness of the Pacific recedes into the night sky, and the lights on the other side of the bridge call out like a finish line to another day that the loneliness is unbearable.

Steve realizes the woman he loves is not able to love him back.

“She’s not able to put both her arms around my shoulders and tell me it’s going to be OK. Not able to go for walks with me. Not able to cook for me. Not able to wake up in the bed next to me. Not able to take care of me when I’m sick.”

“I could go on and on,” Steve said, crying.

“Not able to enjoy life to the extent she was enjoying it before. That’s one of the reasons it was so hard. Because my wife was so full of life. So full of life. So incredibly full of life.”

It’s a late Friday afternoon in August and Kirkpatrick is checking his email.

“Two new vent admissions on Monday,” he said.

That makes three new residents on the subacute unit in as many weeks.

The numbers are growing statewide, too. In 2004, there were just over 2,500 subacute beds eligible for Medi-Cal reimbursement. Today, there are more than 4,700.

And the cost has nearly doubled, from $328 million in 2004, to $636 million in 2013.

There are going to be more beds as our population continues to mature, more baby boomers approaching and going into the later years, just like myself,” Kirkpatrick said.

“I don’t see this as ending.”

Kirkpatrick imagines a time in the future when advance directives become mandatory for anyone signing up for health insurance.

He has seen families struggle with knowing when to let go so often, he’s taken precautions with his own advance directive.

“After seeing so much for the last 35 years, I’ve had enough experience to know I want to make a different choice rather than waiting and hanging in there to see if that miracle could happen.”

But he doesn’t want his wife to be burdened with deciding when to withdraw treatment. So Kirkpatrick has asked someone else to carry out his wishes.

“I’d rather have my wife mad at my best friend than mad at herself,” he said.

Dr. Warm also knows he never wants to be a patient on a subacute unit, and while he’s had the conversation with people close to him, he said he had never written his wishes on paper.

Weeks after our first interview, he makes a confession.

“You know what I had nightmares about after we talked?” he asked.

“I didn’t have an advance directive. And I said that on camera. I’m committed to now sign one.”

Dr. Lawrence Schneiderman lets out a deep sigh when he hears the stories of the people living at Villa Coronado.

Schneiderman is a physician, ethicist and professor emeritus at UC San Diego. He has written extensively on the subject of medical futility and is often asked to consult with hospitals and families when they are making difficult end-of-life decisions.

He doesn’t believe the government should pay for unlimited life-support treatment when there is no reasonable chance of recovery because it isn’t fair to everyone else.

“The money we spend on you for one week, or for one month more of life, could have paid a whole year of decent minimum care for someone else. That’s just not what a just society should do. So you’re just going to have to accept the fact that you had your fair innings.”

Fair innings refers to an argument in bioethics that everyone should have access to their fair share of health care.

Schneiderman believes doctors, not patients or their families, should decide when treatment is futile and withdraw it. He defines futility as a treatment that cannot be appreciated by the patient in any meaningful way.

“The doctor says, ‘Gee, this won’t work. Do you want us to do it? That’s just absurd,” Schneiderman said.

Medicine now is too focused on treating a specific body part, rather than treating the whole person, he said.

“Personhood is better than just being human,” he said. It’s about having wants and desires: knowing who you are, where you are and what you are doing.

“That’s what you really try to protect. Not the fact that you have 46 chromosomes. Not the fact your hair cells are still growing. “

Dr. Michael Kalafer has heard criticism of subacute care. He admits that early in his career as a pulmonologist, he at times was among those who looked down on this type of care.

But now, years later, as the medical director of two subacute units in San Diego, including Villa Coronado, he sees things from a more practical point of view.

“It’s easy to criticize, but what is the alternative?” Kalafer asked.

“We have the folks here. Society has made those decisions. I don’t think our society in California, in the United States, is ready to dictate who gets and doesn’t get life support.”

The best the system can do for now is to provide compassionate care and respect people’s values, Kalafer said.

He believes doctors, himself included, are getting better at having end-of-life conversations.

He comes to terms with his work by asking families the same questions we should all be asking ourselves, he said.

“Is it acceptable to them to be maintained on a machine?

“Is it acceptable to have no ability to enjoy food, but to have all your nourishment through a tube?

“Is it acceptable to depend on others for your basic needs: your toileting, and bathing? Is it acceptable to be out of control over your own environment?

“How much interaction with your environment is important?

“Some people, family and patients, if they can get their loved one to smile at them when they come visit, that’s good enough for them.”

…

Joanne Faryon

is an investigative reporter and producer at

inewsource.

Joanne Faryon

is an investigative reporter and producer at

inewsource.

To contact Joanne, email her at

[email protected].

Follow her on Twitter

@JoanneFaryon.

Brad Racino

is an investigative reporter, videographer, editor,

producer and web designer at inewsource.

Brad Racino

is an investigative reporter, videographer, editor,

producer and web designer at inewsource.

To contact Brad, email him at

[email protected].

Follow him on Twitter

@BradRacino.

Lorie Hearn

is the executive director and editor of

inewsource.

Lorie Hearn

is the executive director and editor of

inewsource.

To contact Lorie, email her at

[email protected].

Follow her on Twitter

@LorieHearn.

FORUM

Have a question about end-of-life care or decision-making? Ask our experts by clicking here. Or, if you’ve had an experience with end-of-life issues, share your story here for possible publication on our website.

FAQ

The Impossible Choice team describes the origin of this project and the difficulties in reporting it here in our Frequently Asked Questions section.

DONATE

An Impossible Choice is a project of inewsource, an independent journalism nonprofit on the campus of San Diego State University. Find out how to support this kind of work here.